I have written many of the essays you've been reading as if art had something to say, and as if it were important. And I believe, more or less - on good days - that something like this is true.

If you've read Citizens, Simon Schama's magnificent history of the French revolution, you will have come across chapter four, "The Cultural Construction of a Citizen." This is the first chapter in which Schama advances in detail the jarring thesis that pre-revolutionary and revolutionary visual arts, from high painting to low propaganda, helped to inspire and guide the revolution. I have thought about this thesis for a very long time now. On the one hand, he draws convincing links. But on the other hand - come on. We're talking about prints, pamphlets, and 18th century French painters.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Girl Making a Dog Dance on Her Bed, 1760, Oil on canvas, 35" x 27.6"

a masterpiece from the pre-revolutionary French genre of fannies-and-puppy-dogs

Usually, my thinking on this odd chapter is that Schama himself is devoted to the visual arts, and overestimates their active role in history to match their active role in his own life. Confusions proliferate from this contrary conclusion as well: if the visual arts are, by and large, of little interest - are they at least of interest to interesting people? Do they shape the lives of the people who shape history? Do these people actually shape history? Should we care what they think?

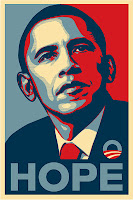

Consider a modern example of the phenomenon Schama describes.

Shepard Fairey, the "Hope" poster, 2008

Everyone would recognize this iconic poster, but I think almost no one would say that its impact shifted the course of the election. It shows correlation, not causation - or at most, it was one of a thousand factors. And yet, in fifty years, when the confusing tangle of antecedent circumstances has faded from memory, and the poster remains as powerful as ever - what role will people imagine it had in the election of 2008?

What do most people know of Barry Goldwater today, apart from Lyndon Johnson's commercial, which bluntly implied that the election of Goldwater would lead to nuclear war?

the "Daisy" commercial, 1964

I have read it argued that this television commercial tipped the balance. Could this be true? I doubt it, just as I doubt that Fairey's poster tipped the balance 44 years later.

I am inclined to believe that the visual arts in the west were most influential in the Middle Ages, when the images hosted by churches helped to describe and explain religion, theology, and philosophy to a largely illiterate populace. This is what I am inclined to believe, but who can accurately reconstruct the hearts of the dead from the documentation they left behind? The documents are the visual arts themselves, and the writings of people to whom the visual arts were important. The reconstruction is impossible, and the documents are skewed. So I have beliefs, but I do not know.

Here's what I do know: whether or not the visual arts make a bit of practical difference to anyone, they do encode intellectual history in complex and sophisticated ways. This makes them a part of our intellectual heritage. Apart from the beauty of art objects, this is one of their key values. They are statements in the great conversation which has gone on since first we spoke until today. History consists in events, but it also consists in ideas. In this second sense, the visual arts do not sway history, nor do they record history. They are the very materials of history.

All this by way of background considerations for a remarkable painting I stumbled across the other day at the Brooklyn Museum. It's among the European paintings in the Beaux-Arts Court, if you want to go see it for yourself.

Carlo Crivelli, Saint James Major, 1472, tempera and gold on panel, 38.3"x12.6"

I had never heard of Carlo Crivelli or Saint James Major. But I'm pretty good at guessing about things. So what do we have here?

The painting has many Medieval trappings: the narrow, centered, vertical saint image - the patterned gold leaf - the stylized angularity of the figure, in whom curves are built up by arpeggios of broken straight lines - and the use of tempera, a pre-oil paint medium.

These are lovely hands, naturalistically rendered with regard to structure and light, and subtly observed down to the level of tendons and vascularity. Renaissance hands. Or consider the feet:

The texture of the sole of the foot is glimpsed on the left foot. Bones and tendons are represented with the exaggerated anatomical detail of the early Renaissance, when artists were still reveling in their ability to pull this kind of stunt at all. The foreshortening of the right foot is plausible and smartly observed. The delicate upward hitch of the big toes is utterly characteristic of the sense of nobility of the period. I am partial to painting feet myself, and I've given their depiction a lot of thought:

Daniel Maidman, Blue Leah #10, 2012, oil on canvas, 24"x24"

Based on James's feet, I'm going to claim that Crivelli, like Mantegna, could and did draw the body in an entirely Renaissance manner. All of his Medieval gestures are choices.

So what's the deal with this painting?

I see this Saint James Major as existing at the crossroads of the intellectual history of the west. Like Botticelli, Crivelli is a man torn between two worlds.

On the one hand, there are the last echoes of the Middle Ages. For all the anthropocentric humanism of Medieval scholastic thought, the heart of the Medieval thinker beat to the Gothic rhythm of puny, cipher-like Man, cringing before the overwhelming force of God's drama as it played itself out across the uncertain face of the fallen world. This intuition of insignificance defined the art of the Middle Ages, its stiff, stereotyped figures tightly integrated into symbolic scenery. This outlook, at its very best - tender, humble, forbearing - Crivelli cannot leave behind. He refuses to leave it behind; he refuses to give up a nearly-obsolete faith.

And yet he is a modern man. All artists are, be they never so reactionary. Crivelli could not help surrendering to the irresistible attractions of the Renaissance. The Medieval figure is an idea playing a role. The Renaissance figure is at most a step removed from direct observation. It is rooted in the perfection of the real. It is so much more convincing, it offers so much more scope for the talents of the artist. Having once seen it, Crivelli is incapable of going back. He must apply it himself. His lighting is realistic, his anatomy is accurate, his flesh is convincing.

The Renaissance glorifies two things: the flesh, and the meaning of the flesh. Crivelli has taken the first carnal step - the glorification of the flesh. But he has not seen all the way to the endpoint of the intuitive ideology of the Renaissance, that meaning arises from the flesh and inheres in it. Instead, he awkwardly sutures his glorious flesh, like a guilty pleasure, into his Medieval pictorial paradigm, in which meaning is imposed from above, as the God of the Middle Ages imposes his will on the world, from above. He pastes a modern man like a decal into a ginned-up old timey composition.

Do you see how exciting this is? This is a platypus of a painting. It is a painting in which clashing elements of different worlds live uneasily side by side. It is only when the boundary of an outlook occurs inside a work, butting up against the boundary of an adjacent outlook, that the contrast makes us intensely aware of the qualities of each. This painting, more than the works that precede or follow it, gives us insights into the deep natures of the Medieval and Renaissance outlooks. It is a little painting, and no doubt many other paintings are better, or illustrate the same principle. But it was in confrontation with this one that I was offered this series of understandings. The painting offered it to me; in an instant, it revived the past and made its concerns clear and present. These are not dead ideas, because we do not yet know the answers to the questions they address. And even if we did, the ideas would not be dead because they are answers generated by our human brothers and sisters, able to speak to us down through the centuries by means of the miracle of their work, which robs time of forgetfulness. That's what art offers: thoughts, beauty, memory, companionship. It does not divert the course of armies, but it compensates us for our sufferings. Importance does not reside in changing history alone. Art rarely changes history, but it is important.

Worth Reading: Citizens, by Simon Schama

Worth Visiting: The Brooklyn Museum

No comments:

Post a Comment